2024-10-09 ノースウェスタン大学

<関連情報>

- https://news.northwestern.edu/stories/2024/10/viruses-are-teeming-on-your-toothbrush-showerhead/

- https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/microbiomes/articles/10.3389/frmbi.2024.1396560/full

- https://microbiomejournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40168-020-00983-x

家庭内バイオフィルムのファージ群集は宿主細菌と相関する Phage communities in household-related biofilms correlate with bacterial hosts

Stefanie Huttelmaier,Weitao Shuai,Jack T. Sumner,Erica M. Hartmann

Frontiers in Microbiomes Published:09 October 2024

DOI:https://doi.org/10.3389/frmbi.2024.1396560

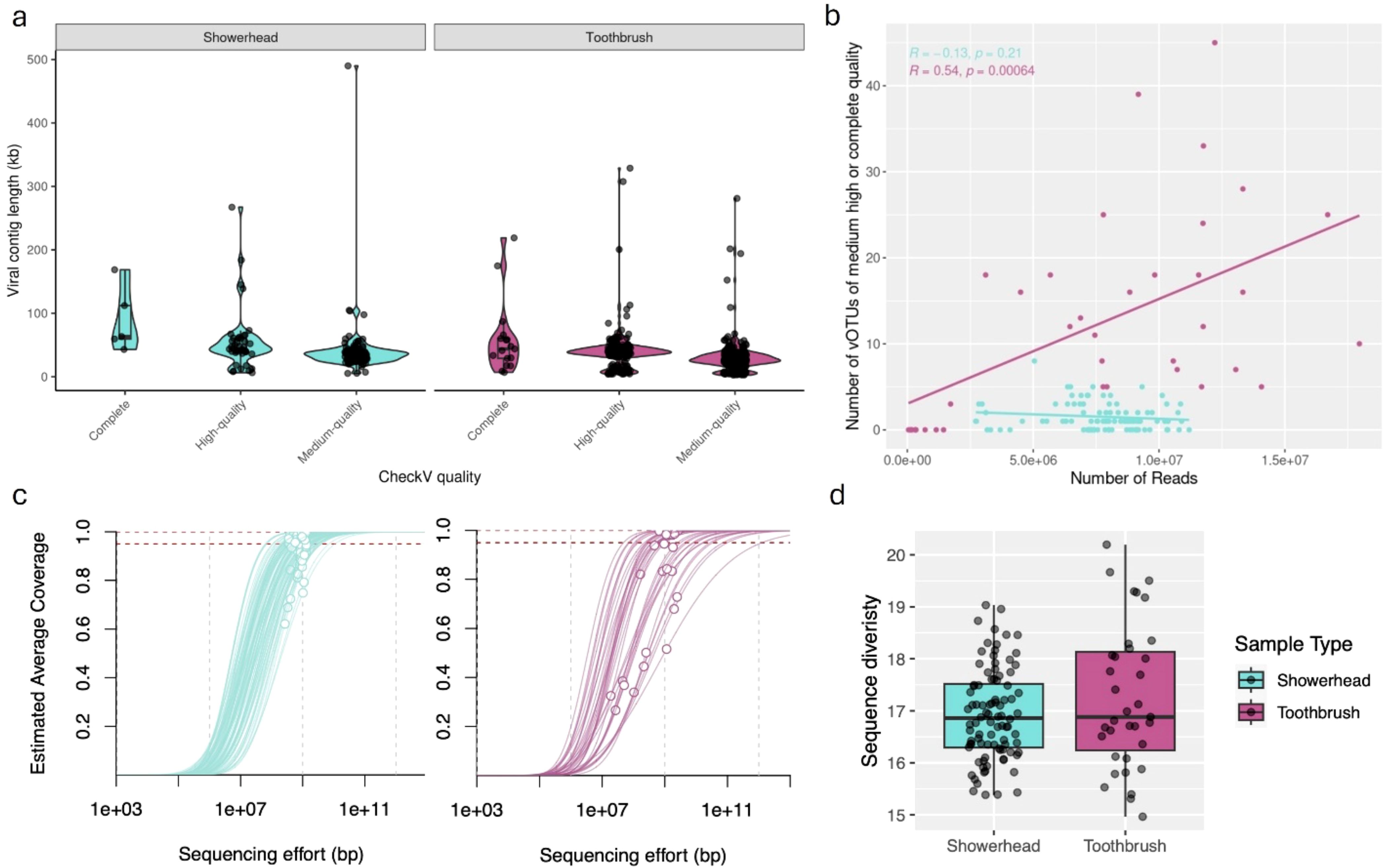

The average American spends 93% of their time in built environments, almost 70% of that is in their place of residence. Human health and well-being are intrinsically tied to the quality of our personal environments and the microbiomes that populate them. Conversely, the built environment microbiome is seeded, formed, and re-shaped by occupant behavior, cleaning, personal hygiene and food choices, as well as geographic location and variability in infrastructure. Here, we focus on the presence of viruses in household biofilms, specifically in showerheads and on toothbrushes. Bacteriophage, viruses that infect bacteria with high host specificity, have been shown to drive microbial community structure and function through host infection and horizontal gene transfer in environmental systems. Due to the dynamic environment, with extreme temperature changes, periods of wetting/drying and exposure to hygiene/cleaning products, in addition to low biomass and transient nature of indoor microbiomes, we hypothesize that phage host infection in these unique built environments are different from environmental biofilm interactions. We approach the hypothesis using metagenomics, querying 34 toothbrush and 92 showerhead metagenomes. Representative of biofilms in the built environment, these interfaces demonstrate distinct levels of occupant interaction. We identified 22 complete, 232 high quality, and 362 medium quality viral OTUs. Viral community richness correlated with bacterial richness but not Shannon or Simpson indices. Of quality viral OTUs with sufficient coverage (614), 532 were connected with 32 bacterial families, of which only Sphingomonadaceae, Burkholderiaceae, and Caulobacteraceae are found in both toothbrushes and showerheads. Low average nucleotide identity to reference sequences and a high proportion of open reading frames annotated as hypothetical or unknown indicate that these environments harbor many novel and uncharacterized phage. The results of this study reveal the paucity of information available on bacteriophage in indoor environments and indicate a need for more virus-focused methods for DNA extraction and specific sequencing aimed at understanding viral impact on the microbiome in the built environment.

歯ブラシのマイクロバイオームがヒト口腔内細菌叢と環境微生物叢の出会いの場となる Toothbrush microbiomes feature a meeting ground for human oral and environmental microbiota

Ryan A. Blaustein,Lisa-Marie Michelitsch,Adam J. Glawe,Hansung Lee,Stefanie Huttelmaier,Nancy Hellgeth,Sarah Ben Maamar & Erica M. Hartmann

Microbiome Published:31 January 2021

DOI:https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-020-00983-x

Abstract

Background

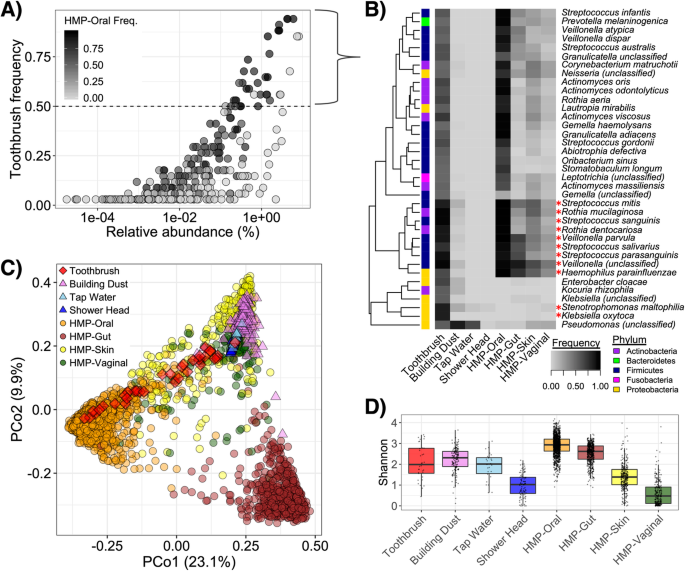

While indoor microbiomes impact our health and well-being, much remains unknown about taxonomic and functional transitions that occur in human-derived microbial communities once they are transferred away from human hosts. Toothbrushes are a model to investigate the potential response of oral-derived microbiota to conditions of the built environment. Here, we characterize metagenomes of toothbrushes from 34 subjects to define the toothbrush microbiome and resistome and possible influential factors.

Results

Toothbrush microbiomes often comprised a dominant subset of human oral taxa and less abundant or site-specific environmental strains. Although toothbrushes contained lower taxonomic diversity than oral-associated counterparts (determined by comparison with the Human Microbiome Project), they had relatively broader antimicrobial resistance gene (ARG) profiles. Toothbrush resistomes were enriched with a variety of ARGs, notably those conferring multidrug efflux and putative resistance to triclosan, which were primarily attributable to versatile environmental taxa. Toothbrush microbial communities and resistomes correlated with a variety of factors linked to personal health, dental hygiene, and bathroom features.

Conclusions

Selective pressures in the built environment may shape the dynamic mixture of human (primarily oral-associated) and environmental microbiota that encounter each other on toothbrushes. Harboring a microbial diversity and resistome distinct from human-associated counterparts suggests toothbrushes could potentially serve as a reservoir that may enable the transfer of ARGs.