2025-12-19 シカゴ大学

Simulations showed that sound waves applied to the eardrum of “Thrinaxodon” (top) would have enabled it to hear much more effectively than through bone conduction alone (bottom). Infographic courtesy of April I. Neander, Alec Wilken

<関連情報>

- https://news.uchicago.edu/story/fossil-study-rewrites-timeline-evolution-hearing-mammals

- https://www.pnas.org/doi/abs/10.1073/pnas.2516082122

キノドン類トリナクソドンの下顎中耳の生体力学と哺乳類の聴覚の進化 Biomechanics of the mandibular middle ear of the cynodont Thrinaxodon and the evolution of mammal hearing

Alec T. Wilken, Chelsie C. G. Snipes, Callum F. Ross, and Zhe-Xi Luo

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Published:December 8, 2025

DOI:https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2516082122

Significance

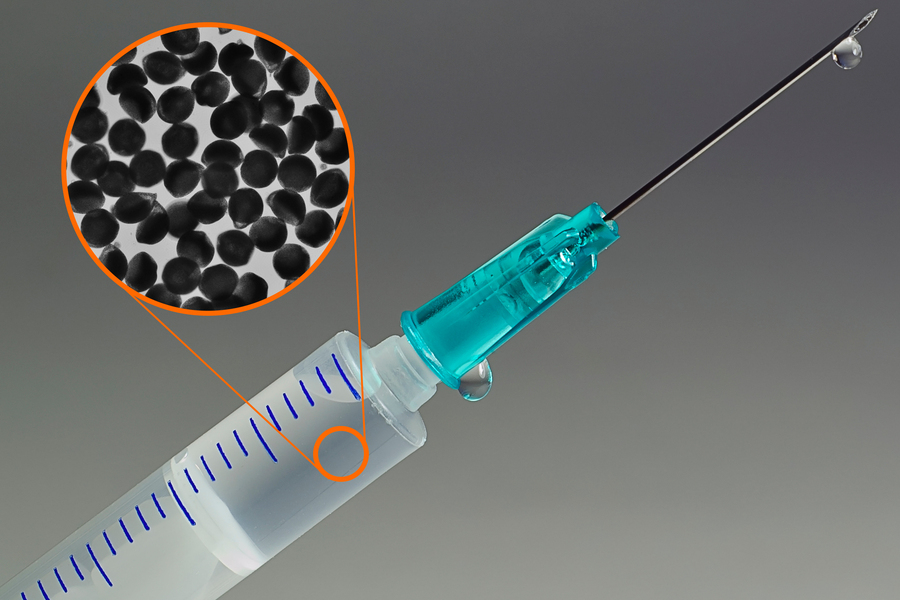

The middle ear of modern mammals is detached from the mandible and has a soft-tissue eardrum, which allows airborne sound to be heard across a wide range of frequencies. A rich fossil record shows that the middle ear bones of mammals evolved from the jaw bones of their synapsid predecessors, but how this transformation was associated with changes in hearing function is unknown. Our finite element analysis (FEA) of the harmonic response of the mandibular ear bones and soft-tissue eardrum of the synapsid Thrinaxodon suggests that this 250-Mya-old mammal precursor was already capable of tympanic hearing similar to extant mammals and provides evidence that this functional transition occurred very early in mammal evolutionary history.

Abstract

The middle ear of mammals is a major functional innovation, distinctive in that it is detached from the mandible and has a tympanic membrane supported by a ring-like ectotympanic. These novelties of the middle ear have enabled modern mammals to develop more sensitive hearing than all other tetrapods, especially at higher frequencies. Fossils from recent decades have clarified the evolution of the detached middle ear from the jaw bones of Paleozoic therapsids and Mesozoic cynodonts, and the evolution of the tympanum. These discoveries make it possible to answer important questions about the functional significance of these features. Here, we evaluate the relative hearing efficacy of a well-known cynodont precursor to mammals, Thrinaxodon liorhinus. Using finite element analysis (FEA), we calculated the harmonic response of the Thrinaxodon ear to bone-conducted and airborne sound and estimated the sound pressure level (SPL) at the stapedial footplate across a broad range of frequencies. We provide evidence that airborne sound received at the tympanum was the most effective mode of sound reception in Thrinaxodon. In contrast, bone conducted sound through the mandibular bones barely met our estimated hearing threshold. Our findings suggest that, like modern mammals, cynodonts were already reliant on a soft tissue tympanum to receive airborne sound, albeit with limited sensitivity to high frequencies. This is a detailed biomechanical evaluation of tympanum function in the cynodont predecessors of mammals and yields insight into the sequence of functional innovations during the evolution of mammal hearing.