2025-06-16 マウントサイナイ医療システム(MSHS)

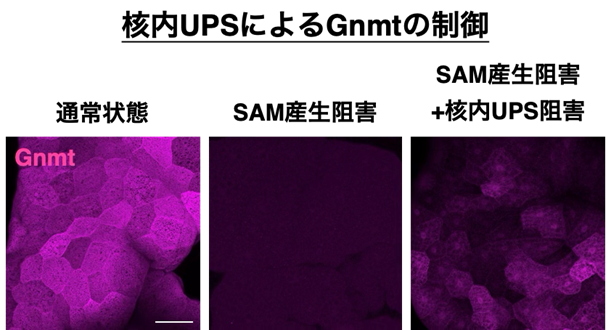

Wearable device measured changes in sleep trajectories over the 45 days before and 45 days after an IBD flare up (Figure 3). Courtesy of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

<関連情報>

- https://www.mountsinai.org/about/newsroom/2025/mount-sinai-researchers-use-wearable-technology-to-explore-the-link-between-ibd-and-sleep-disruption

- https://www.cghjournal.org/article/S1542-3565(25)00522-1/abstract

ウェアラブルデバイスが活動性炎症性腸疾患における睡眠特性の変化と睡眠軌跡を同定する Wearable Devices Identify Altered Sleep Characteristics and Sleep Trajectories in Active Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Robert P. Hirten, MD ∙ Matteo Danieletto, PhD, ∙ Jessica K. Whang, MS ∙ … ∙ Mariana G. Figueiro, PhD ∙ Bruce E. Sands, MD ∙ Mayte Suarez-Farinas, PhD

Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology Published:June 26, 2025

DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2025.06.003

Abstract:

Background and Aims

Poor sleep is associated with flares of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Studies often rely on subjective assessments of sleep and disease activity. Our aim is to use wearable devices to objectively assess the impact of inflammation and symptoms on sleep architecture in IBD.

Methods

Individuals ≥18 years old, diagnosed with and on medication for IBD, were enrolled in an observational study, answered daily disease activity surveys and wore a wearable device. Sleep architecture, sleep efficiency and total hours asleep were collected from the devices. Inflammatory markers were collected as standard of care. Associations between sleep metrics and periods of symptomatic and inflammatory flares and combinations of symptomatic and inflammatory activity were compared to periods of symptomatic and inflammatory remission. The rate of change in sleep metrics for 45 days before and after inflammatory and symptomatic flares were explored.

Results

101 participants were enrolled contributing a mean duration of 228.16 (SD 154.24) nights of wearable data. Periods with active inflammation were associated with a significantly smaller percentage of sleep time in rapid eye movement (REM) and a greater percentage of sleep time in light sleep. Evaluating the intersection of inflammatory and symptomatic flares, altered sleep architecture was only evident when inflammation was present, and not with symptoms. Significant differences were observed in the rate that the percentage of time spent in deep and light sleep changed before and after inflammatory and symptomatic flares.

Conclusions

Impaired sleep architecture is associated with inflammatory activity in IBD, and the presence of symptomatic flares alone does not impact sleep quality.