2023-09-20 ワシントン州立大学(WSU)

◆この研究結果は、鳥の個体数が急速に減少しているアメリカ全体における保護活動に影響を与える可能性があります。都市部の鳥は都市環境に適応する可能性がある一方で、渡り鳥は冬を過ごす場所が都市の明るい光や騒音の影響を受けにくいため、都市生活に適応するのが難しいかもしれないとのこと。

◆研究では、都市部と都市外部の鳥の体と目のサイズを比較し、明るさや騒音の測定も行われました。都市部の明るい光に対する鳥の目のサイズの適応が示唆され、都市環境での鳥の生存に影響を及ぼす可能性があるとされています。

<関連情報>

- https://news.wsu.edu/press-release/2023/09/20/urban-light-pollution-linked-to-smaller-eyes-in-birds/

- https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/gcb.16935

- https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.aaw1313

都市化の表現型?渡り鳥ではなく、留鳥の目の大きさは都市に関連する光害レベルによって変化する。 Phenotypic signatures of urbanization? Resident, but not migratory, songbird eye size varies with urban-associated light pollution levels

Todd M. Jones, Alfredo P. Llamas, Jennifer N. Phillips

Global Change Biology Published: 20 September 2023

DOI:https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.16935

Abstract

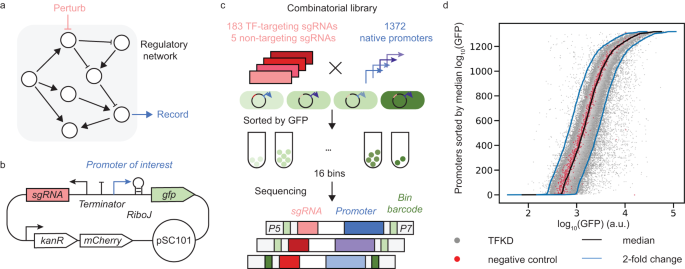

Urbanization now exposes large portions of the earth to sources of anthropogenic disturbance, driving rapid environmental change and producing novel environments. Changes in selective pressures as a result of urbanization are often associated with phenotypic divergence; however, the generality of phenotypic change remains unclear. In this study, we examined whether morphological phenotypes in two residential species (Carolina Wren [Thryothorus ludovicianus] and Northern Cardinal [Cardinalis cardinalis]) and two migratory species (Painted Bunting [Passerina ciris], and White-eyed Vireo [Vireo griseus]), differed between urban core and edge habitats in San Antonio, Texas, USA. More specifically, we examined whether urbanization, associated sensory pollution (light and noise) and brightness (open, bright areas cause by anthropogenic land use) influenced measures of avian body (mass and frame size) and lateral eye size. We found no differences in body size between urban core and edge habitats for all species except the Painted Bunting, in which core-urban individuals were smaller. Rather than a direct effect of urbanization, this was due to differences in age structure between habitats, with urban-core areas consisting of higher proportions of younger buntings which are, on average, smaller than older birds. Residential birds inhabiting urban-core areas had smaller eyes compared to their urban-edge counterparts, resulting from a negative association between eye size and light pollution and brightness across study sites; notably, we found no such association in the two migratory species. Our findings demonstrate how urbanization may indirectly influence phenotypes by altering population demographics and highlight the importance of accounting for age when assessing factors driving phenotypic change. We also provide some of the first evidence that birds may adapt to urban environments through changes in their eye morphology, demonstrating the need for future research into relationships among eye size, ambient light microenvironment use, and disassembly of avian communities as a result of urbanization.

北米の鳥類相の減少 Decline of the North American avifauna

Kenneth V. Rosenberg* ,Adriaan M. Dokter ,Peter J. Blancher,John R. Sauer ,Adam C. Smith ,Paul A. Smith ,Jessica C. Stanton ,Arvind Panjabi ,Laura Helft ,Michael Parr ,and Peter P. Marra

Science Published:19 Sep 2019

DOI:https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaw1313

Staggering decline of bird populations

Because birds are conspicuous and easy to identify and count, reliable records of their occurrence have been gathered over many decades in many parts of the world. Drawing on such data for North America, Rosenberg et al. report wide-spread population declines of birds over the past half-century, resulting in the cumulative loss of billions of breeding individuals across a wide range of species and habitats. They show that declines are not restricted to rare and threatened species—those once considered common and wide-spread are also diminished. These results have major implications for ecosystem integrity, the conservation of wildlife more broadly, and policies associated with the protection of birds and native ecosystems on which they depend.

Abstract

Species extinctions have defined the global biodiversity crisis, but extinction begins with loss in abundance of individuals that can result in compositional and functional changes of ecosystems. Using multiple and independent monitoring networks, we report population losses across much of the North American avifauna over 48 years, including once-common species and from most biomes. Integration of range-wide population trajectories and size estimates indicates a net loss approaching 3 billion birds, or 29% of 1970 abundance. A continent-wide weather radar network also reveals a similarly steep decline in biomass passage of migrating birds over a recent 10-year period. This loss of bird abundance signals an urgent need to address threats to avert future avifaunal collapse and associated loss of ecosystem integrity, function, and services.