2022-02-22 ペンシルベニア州立大学(PennState)

しかし、今回の研究で、研究者たちは、実際の最高湿球温度は、若くて健康な被験者であっても、湿球温度約31℃(湿度100%で華氏87度)より低いことを発見しました。暑さに弱い高齢者の場合は、さらに低い温度である可能性が高い。

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — As climate change nudges the global temperature higher, there is rising interest in the maximum environmental conditions like heat and humidity to which humans can adapt. New Penn State research found that in humid climates, that temperature may be lower than previously thought.

It has been widely believed that a 35°C wet-bulb temperature (equal to 95°F at 100% humidity or 115°F at 50% humidity) was the maximum a human could endure before they could no longer adequately regulate their body temperature, which would potentially cause heat stroke or death over a prolonged exposure.

Wet-bulb temperature is read by a thermometer with a wet wick over its bulb and is affected by humidity and air movement. It represents a humid temperature at which the air is saturated and holds as much moisture as it can in the form of water vapor; a person’s sweat will not evaporate at that skin temperature.

But in their new study, the researchers found that the actual maximum wet-bulb temperature is lower — about 31°C wet-bulb or 87°F at 100% humidity — even for young, healthy subjects. The temperature for older populations, who are more vulnerable to heat, is likely even lower.

W. Larry Kenney, professor of physiology and kinesiology and Marie Underhill Noll Chair in Human Performance, said the results could help people better plan for extreme heat events, which are occurring more frequently as the world warms.

“If we know what those upper temperature and humidity limits are, we can better prepare people — especially those who are more vulnerable — ahead of a heat wave,” Kenney said. “That could mean prioritizing the sickest people who need care, setting up alerts to go out to a community when a heatwave is coming, or developing a chart that provides guidance for different temperature and humidity ranges.”

Kenney added that it’s important to note that using this temperature to assess risk only makes sense in humid climates. In drier climates sweat is able to evaporate from the skin, which helps cool body temperature. Unsafe dry heat environments rely more on the temperature and the ability to sweat, and less on the humidity.

The study was recently published in the Journal of Applied Physiology.

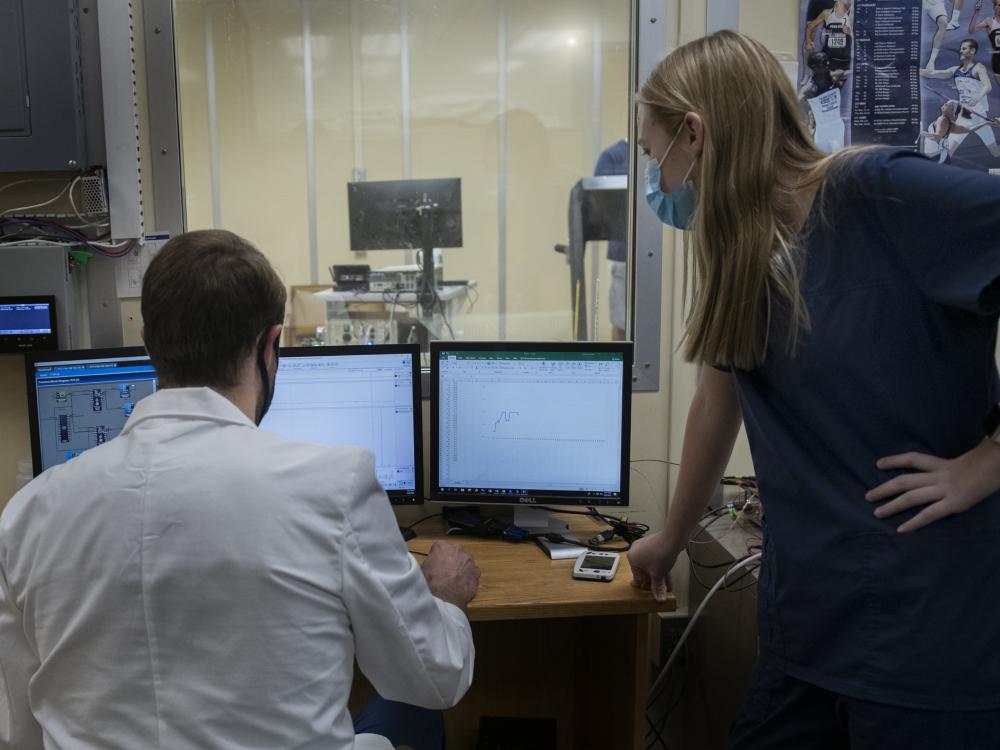

S. Tony Wolf, postdoctoral researcher in Kinesiology at Penn State, right, and Rachel Cottle, graduate student in exercise physiology, discuss the data collected during a session in the lab. Credit: Patrick Mansell / Penn State. Creative Commons

EXPAND

According to the researchers, while previous studies have theorized that a 35°C wet-bulb temperature was the upper limit of human adaptability, that temperature was based on theory and modeling and not real-world data from humans.

Kenney said that he and the other researchers wanted to evaluate this theoretical temperature as part of the PSU H.E.A.T. (Human Environmental Age Thresholds) project, which is examining how hot and humid an environment has to be before older adults start to have problems tolerating heat stress.

“If you look at heat wave statistics, most of the people who die during heat waves are older people,” Kenney said. “The climate is changing, so there are going to be more — and more severe — heat waves. The population is also changing, so there are going to be more older adults. And so it’s really important to study the confluence of those two shifts.”

For this study, the researchers recruited 24 participants between the ages of 18 and 34. While the researchers plan to also perform these experiments in older adults, they wanted to start with younger people.

“Young, fit, healthy people tend to tolerate heat better, so they will have a temperature limit that can function as the ‘best case’ baseline,” Kenney said. “Older people, people on medications, and other vulnerable populations will likely have a tolerance limit below that.”

Prior to the experiment, each participant swallowed a tiny radio telemetry device encased in a capsule that would then measure their core temperature throughout the experiment.

Then, the participant entered a specialized environmental chamber that had adjustable temperature and humidity levels. While the participant performed light physical activity like light cycling or walking slowly on a treadmill, the chamber either gradually increased in temperature or in humidity until the participant reached a point at which their body could no longer maintain its core temperature.

After analyzing their data, the researchers found that critical wet-bulb temperatures ranged from 25°C to 28°C in hot-dry environments and from 30°C to 31°C in warm-humid environments — all lower than 35°C wet-bulb.

“Our results suggest that in humid parts of the world, we should start to get concerned — even about young, healthy people — when it’s above 31 degrees wet-bulb temperature,” Kenney said. “As we continue our research, we’re going to explore what that number is in older adults, as it will probably be even lower than that.”

Additionally, the researchers added that because humans adapt to heat differently depending on the humidity level, there is likely not a single cutoff limit that can be set as the “maximum” that humans can endure across all environments found on Earth.

S. Tony Wolf, postdoctoral researcher in kinesiology at Penn State; Daniel J. Vecellio, postdoctoral fellow at Penn State’s Center for Healthy Aging; and Rachel M. Cottle, graduate student in exercise physiology at Penn State, also participated in this work.

The National Institute on Aging at the National Institutes of Health helped support this research.