2025-07-09 イェール大学

A life reconstruction of the specimen of Citipati, a dinosaur closely related to birds, analyzed with an x-ray cutaway of the specimen’s wrist. The small and rounded pisiform is highlighted in blue. Credit: Henry S. Sharpe/University of Alberta

<関連情報>

- https://news.yale.edu/2025/07/09/wrists-twist-its-link-between-dinosaurs-and-birds

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-09232-3

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s41559-022-01699-x

- https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.abb4305

獣脚類の手首の再編成が鳥類の飛行の起源に先行していた Reorganization of the theropod wrist preceded the origin of avian flight

James G. Napoli,Matteo Fabbri,Alexander A. Ruebenstahl,Jingmai K. O’Connor,Bhart-Anjan S. Bhullar & Mark A. Norell

Nature Published:09 July 2025

DOI:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09232-3

Abstract

The carpus (wrist) of birds has a complex evolutionary history, long known to involve carpal reduction and recently shown to include topological replacement of one carpal (the ulnare) by another (the pisiform)1. The pisiform plays a crucial role in stabilization of the distal wingtip during flight2, and facilitates kinematic integration that ‘automates’ wing motion3. The apparent absence of a pisiform in all but the earliest theropod dinosaurs led to the proposal that it was lost early in theropod evolution and regained only in birds as a key step in the origin of flight1. Here, we describe the forelimb skeletons of two newly prepared theropod dinosaur specimens from the Gobi Desert of Mongolia, each of which preserves a pisiform, establishing its presence in Oviraptorosauria and Troodontidae in addition to birds. Reinterpretation of published material in light of these specimens shows a pisiform in a wide range of theropod species, including Microraptor4, Ambopteryx5 and Anchiornis6. Our results indicate that the pisiform replaced the ulnare by origin of the clade Pennaraptora, phylogenetically coincident with the hypothesized origin(s) of flight in birds and their closest relatives7,8. Taken together, our results indicate that replacement of the ulnare by the pisiform was a terminal step in assembly of the dinosaurian flight apparatus that occurred close to the origins of flight in theropod dinosaurs, rather than a novelty restricted to birds.

無脊椎動物前肢筋のホモロジーが明らかになった胚性筋分裂パターン Embryonic muscle splitting patterns reveal homologies of amniote forelimb muscles

Daniel Smith-Paredes,Miccaella E. Vergara-Cereghino,Arianna Lord,Malcolm M. Moses,Richard R. Behringer & Bhart-Anjan S. Bhullar

Nature Ecology & Evolution Published:21 March 2022

DOI:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-022-01699-x

Abstract

Limb muscles are remarkably complex and evolutionarily labile. Although their anatomy is of great interest for studies of the evolution of form and function, their homologies among major amniote clades have remained obscure. Studies of adult musculature are inconclusive owing to the highly derived morphology of modern amniote limbs but correspondences become increasingly evident earlier in ontogeny. We followed the embryonic development of forelimb musculature in representatives of six major amniote clades and found, contrary to current consensus, that these early splitting patterns are highly conserved across Amniota. Muscle mass cleavage patterns and topology are highly conserved in reptiles including birds, irrespective of their skeletal modifications: the avian flight apparatus results from slight early topological modifications that are exaggerated during ontogeny. Therian mammals, while conservative in their cleavage patterns, depart drastically from the ancestral amniote musculoskeletal organization in terms of topology. These topological changes occur through extension, translocation and displacement of muscle groups later in development. Overall, the simplicity underlying the apparent complexity of forelimb muscle development allows us to resolve conflicting hypotheses about homology and to trace the history of each individual forelimb muscle throughout the amniote radiations.

鳥類のような内耳の初期の起源と恐竜の運動と発声の進化 The early origin of a birdlike inner ear and the evolution of dinosaurian movement and vocalization

Michael Hanson, Eva A. Hoffman, Mark A. Norell, and Bhart-Anjan S. Bhullar

Science Published:7 May 2021

DOI:https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abb4305

Revealing behavioral secrets in extinct species

Extinct species had complex behaviors, just like modern species, but fossils generally reveal little of these details. New approaches that allow for the study of structures that relate directly to behavior are greatly improving our understanding of the lifestyles of extinct animals (see the Perspective by Witmer). Hanson et al. looked at three-dimensional scans of archosauromorph inner ears and found clear patterns relating these bones to complex movement, including flight. Choiniere et al. looked at inner ears and scleral eye rings and found a clear emergence of patterns relating to nocturnality in early theropod evolution. Together, these papers reveal behavioral complexity and evolutionary patterns in these groups.

Science, this issue p. 601, p. 610; see also p. 575

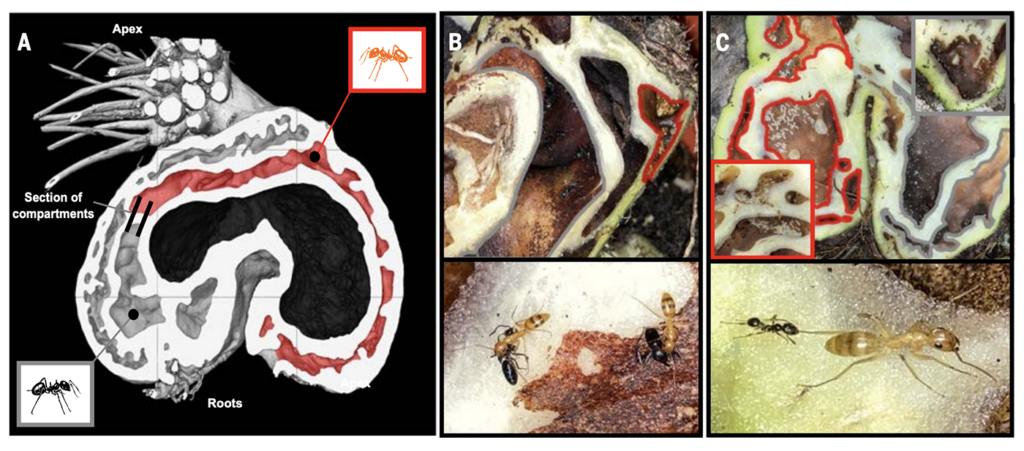

Abstract

Reptiles, including birds, exhibit a range of behaviorally relevant adaptations that are reflected in changes to the structure of the inner ear. These adaptations include the capacity for flight and sensitivity to high-frequency sound. We used three-dimensional morphometric analyses of a large sample of extant and extinct reptiles to investigate inner ear correlates of locomotor ability and hearing acuity. Statistical analyses revealed three vestibular morphotypes, best explained by three locomotor categories—quadrupeds, bipeds and simple fliers (including bipedal nonavialan dinosaurs), and high-maneuverability fliers. Troodontids fall with Archaeopteryx among the extant low-maneuverability fliers. Analyses of cochlear shape revealed a single instance of elongation, on the stem of Archosauria. We suggest that this transformation coincided with the origin of both high-pitched juvenile location, alarm, and hatching-synchronization calls and adult responses to them.