2025-04-25 東京大学

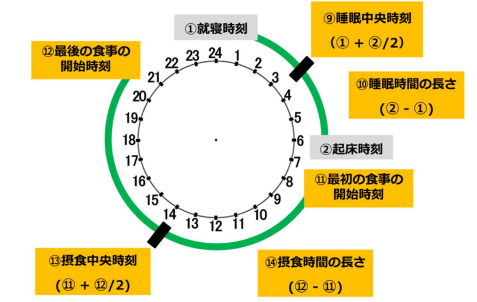

時間栄養学における主要な項目である睡眠中央時刻、睡眠時間の長さ、摂食中央時刻、摂食時間の長さ

<関連情報>

- https://www.u-tokyo.ac.jp/content/400263122.pdf

- https://ijbnpa.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12966-025-01740-9

クロノ栄養行動質問票(CNBQ)と11日間のイベントベースの生態学的瞬間評価による摂食日誌との相対的妥当性 Relative validity of the Chrono-Nutrition Behavior Questionnaire (CNBQ) against 11-day event-based ecological momentary assessment diaries of eating

Kentaro Murakami,Nana Shinozaki,Tracy A. McCaffrey,M. Barbara E. Livingstone,Shizuko Masayasu & Satoshi Sasaki

International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity Published:25 April 2025

DOI:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-025-01740-9

Abstract

Background

A growing number of studies have investigated chrononutrition-related variables in relation to health outcomes. However, only a few questionnaires specifically designed for assessing chrononutrition-related parameters have been validated. We aimed to examine the relative validity of the Chrono-Nutrition Behavior Questionnaire (CNBQ) against 11-day event-based ecological momentary assessment (EMA) diaries of eating.

Methods

Informed by previous research, we developed the CNBQ for the comprehensive assessment of chrononutrition-related parameters, including sleep variables, eating frequency, timing of eating, duration of eating occasions, duration of eating windows, and time interval between sleep and eating, for workdays and non-workdays separately. Between February and April 2023, a total of 1050 Japanese adults aged 20–69 years completed the online CNBQ and subsequently kept event-based EMA food diaries for 11 days, including 6.5 workdays and 4.5 non-workdays on average.

Results

Mean differences between estimates derived from the CNBQ and the EMA food diaries were < 10% for most of the variables examined, both for workdays (27 of 33; 82%) and non-workdays (25 of 33; 76%), and for variables based on differences between workdays and non-workdays, such as eating jetlag (5 of 6; 83%). Spearman correlation coefficients between estimates based on the CNBQ and estimates based on the EMA food diaries were ≥ 0.50 for 26 variables (79%) on workdays and 22 variables (67%) on non-workdays (e.g., mid-sleep time; total eating frequency; timing of first eating occasion, last eating occasion, first meal, and last meal; duration of first meal and last meal; duration of eating window; eating midpoint; and time interval between wake time and first eating occasion and between last meal and sleep time), and 2 variables based on differences between workdays and non-workdays (e.g., eating jetlag base on breakfast timing). Bland–Altman analysis showed that the limits of agreement were wide and that the bias of overestimation by the CNBQ was proportional as mean estimates of the CNBQ and EMA food diaries increased.

Conclusions

These findings suggest that the relative validity of the CNBQ justifies its use in estimating mean values and ranking individuals for the majority of chrononutrition-related parameters.