2024-07-04 カリフォルニア大学サンディエゴ校(UCSD)

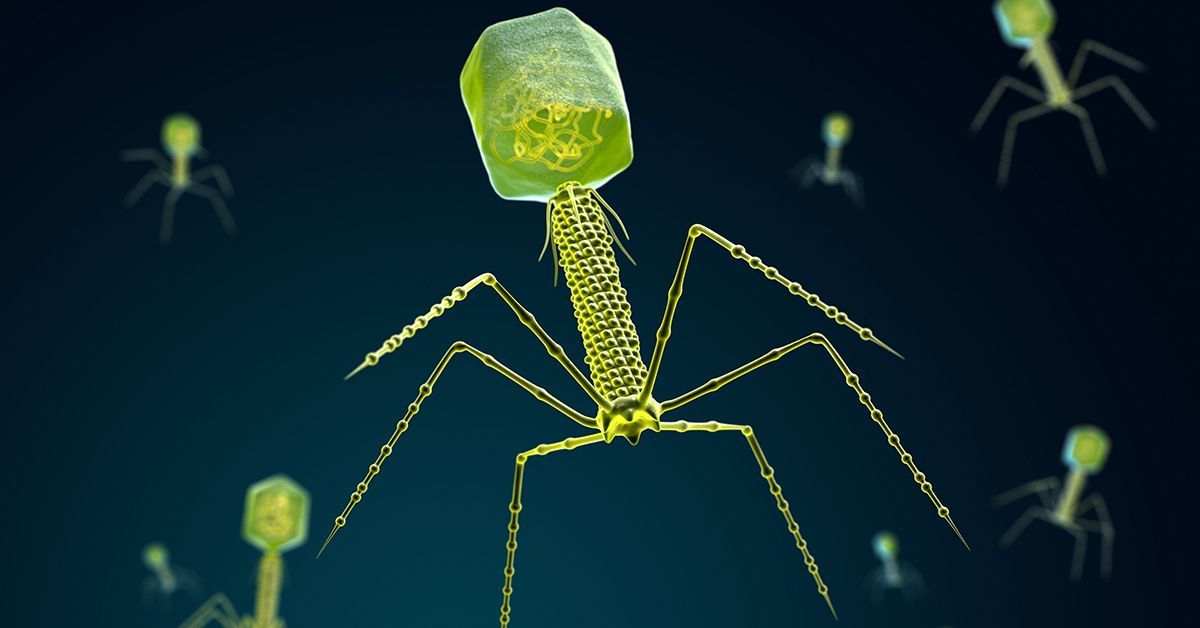

Bacteriophages, seen here in an artist’s illustration, are the most abundant organisms on Earth. UC San Diego researchers studying these viruses were surprised to find that pieces of DNA known as ‘selfish genetic elements’ play a crucial role in competition with other bacteriophages. Credit: iStock/iLexx

Bacteriophages, seen here in an artist’s illustration, are the most abundant organisms on Earth. UC San Diego researchers studying these viruses were surprised to find that pieces of DNA known as ‘selfish genetic elements’ play a crucial role in competition with other bacteriophages. Credit: iStock/iLexx

<関連情報>

- https://today.ucsd.edu/story/not-so-selfish-after-all-viruses-use-freeloading-genes-as-weapons

- https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adl1356

- https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2321190121 (https://medibio.tiisys.com/126392/)

イントロン・エンドヌクレアーゼがコインインフェクションウイルス間の干渉競争を促進する An intron endonuclease facilitates interference competition between coinfecting viruses

ERICA A. BIRKHOLZ, CHASE J. MORGAN, THOMAS G. LAUGHLIN, REBECCA K. LAU, […], AND JOE POGLIANO

Science Published:4 Jul 2024

DOI:https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adl1356

Editor’s summary

Viruses frequently harbor mobile introns containing homing endonucleases, but their function or selective advantage is in doubt. Birkholz et al. have discovered that a mobile intron containing a homing endonuclease found within a viral RNA polymerase gene in one bacteriophage blocks productive infection by a related and competing coinfecting bacteriophage. The homing endonuclease of one phage aims for the homologous sequence in the polymerase of the competitor phage to block assembly of the rival’s progeny. Competition experiments confirmed that even small selective advantages such as this are quickly amplified because of the rapid rates of viral replication. Similar mobile introns are ubiquitous across phage, fungi, and archaea, and may provide selective advantages in a range of interactions. —Caroline Ash

Abstract

Introns containing homing endonucleases are widespread in nature and have long been assumed to be selfish elements that provide no benefit to the host organism. These genetic elements are common in viruses, but whether they confer a selective advantage is unclear. In this work, we studied intron-encoded homing endonuclease gp210 in bacteriophage ΦPA3 and found that it contributes to viral competition by interfering with the replication of a coinfecting phage, ΦKZ. We show that gp210 targets a specific sequence in ΦKZ, which prevents the assembly of progeny viruses. This work demonstrates how a homing endonuclease can be deployed in interference competition among viruses and provide a relative fitness advantage. Given the ubiquity of homing endonucleases, this selective advantage likely has widespread evolutionary implications in diverse plasmid and viral competition as well as virus-host interactions.

核形成ファージがコードする必須かつ高度に選択的なタンパク質輸入経路 An essential and highly selective protein import pathway encoded by nucleus-forming phage

Chase J. Morgan, Eray Enustun, Emily G. Armbruster, +16, and Joe Pogliano

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Published:April 30, 2024

DOI:https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2321190121

Significance

The phage nucleus is an enclosed replication compartment built by Chimalliviridae phages that, similar to the eukaryotic nucleus, separates transcription from translation and selectively imports certain proteins. This allows the phage to concentrate proteins required for DNA replication and transcription while excluding DNA-targeting host defense proteins. However, the mechanism of selective trafficking into the phage nucleus is currently unknown. Here, we determine the region of a phage nuclear protein that targets it for nuclear import and identify a conserved, essential nuclear shell-associated protein that plays a key role in this process. This work provides a mechanistic model of selective import into the phage nucleus.

Abstract

Targeting proteins to specific subcellular destinations is essential in prokaryotes, eukaryotes, and the viruses that infect them. Chimalliviridae phages encapsulate their genomes in a nucleus-like replication compartment composed of the protein chimallin (ChmA) that excludes ribosomes and decouples transcription from translation. These phages selectively partition proteins between the phage nucleus and the bacterial cytoplasm. Currently, the genes and signals that govern selective protein import into the phage nucleus are unknown. Here, we identify two components of this protein import pathway: a species-specific surface-exposed region of a phage intranuclear protein required for nuclear entry and a conserved protein, PicA (Protein importer of chimalliviruses A), that facilitates cargo protein trafficking across the phage nuclear shell. We also identify a defective cargo protein that is targeted to PicA on the nuclear periphery but fails to enter the nucleus, providing insight into the mechanism of nuclear protein trafficking. Using CRISPRi-ART protein expression knockdown of PicA, we show that PicA is essential early in the chimallivirus replication cycle. Together, our results allow us to propose a multistep model for the Protein Import Chimallivirus pathway, where proteins are targeted to PicA by amino acids on their surface and then licensed by PicA for nuclear entry. The divergence in the selectivity of this pathway between closely related chimalliviruses implicates its role as a key player in the evolutionary arms race between competing phages and their hosts.